Worldbuilding Guide: Nautical Pt. 1 - Onboard Orientation

Writing stories with boats or ships? Start here!

Note: this subject matter requires some images and figures which increase the email size. For best experience, open this article in your browser or the Substack app.

Hello! I’m Ian Dunmore, and this is Dunmore Dispatch.

Normally I’m on here writing fantasy short stories, but I’m going to take a short break to write a worldbuilding and fiction guide for all things maritime!

The goal of this guide is to provide writers a jump-off point to understanding the nautical-faring world.

In that goal, it will fail you. The world of boats, ships, and water is too large to be neatly circumscribed.

The good news is that, as a writer, you don’t need to know how to sail across the Atlantic — you just need to know enough to compellingly write about it. That’s what this guide is for.

In Part 1: Basic Terms, we’ll be covering some fundamental governing jargon (with a few fun and edifying digressions) to help you get your sailor legs. It will begin with orientation, moving into decks, then get a little into maneuvering and conclude with a note on structure. This progression is meant to capture information your average sailor would immediately recognize and be familiar with. Put bluntly, by the end of this you should be able to write relatively coherent sailor dialogue.

Subsequent weeks will handle sails and navigational considerations.

We’ll be learning a lot of new words, but the good news is that many of the terms double-back on themselves as you progress, so the memorization compounds.

There are also sometimes terms that mean almost the same thing, which I’ll try and highlight and give examples of usage.

It gets easier, I promise.

Let’s dive in.

Onboard Orientation

Many nautical terms have opposite or complementary partnerships to them, and I find it useful to learn them in pairs (or trios, or sometimes quartets or… quintets?).

Bow and Stern

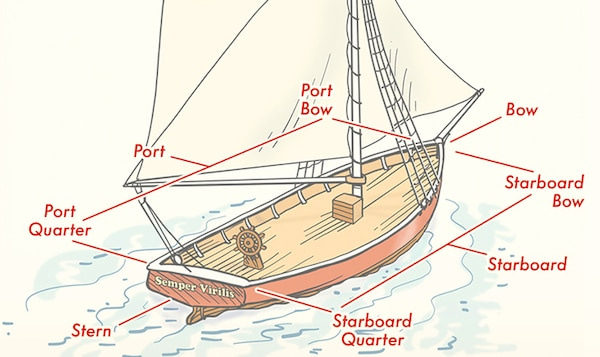

The front of a ship is the bow, and the rear is the stern.

You might sometimes hear the rear get called the quarter, but this more pertains to the corners — which I’ll cover further down when we talk about decks — as opposed to the stern which is the extreme back.

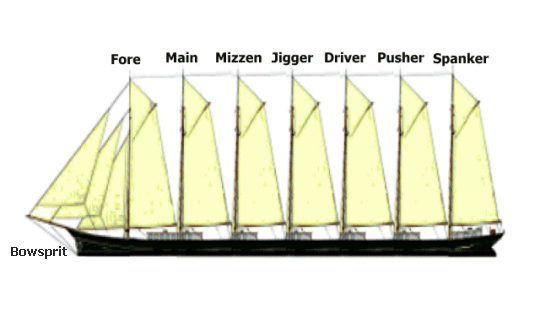

It will also be useful here to learn the name of the frontmost part of the keel, sort of a fillet along the ship’s front that terminates at that pointy thing. This fillet is called the stem, while the pointy thing is the bowsprit — I hope I can eventually get into nautical warfare, but I do want to say right here that the purpose of the bowsprit was for rigging jib sails, not for doing stabby-stabs against enemy ships! A ram was a very different structure indeed, and any ship that tried doing that with a bowsprit would be in for a very bad time and probably earn the ridicule of all its piers (see what I did there?).

The stem sometimes gets referred to as the extreme front of the ship in lieu of the bow, i.e. “stem to stern,” but this is more expressive than literal, a bit like referring to the whole of a car body as “fender to bumper” or one’s whole anatomy as “head to toe.”

The middle of the ship is typically referred to as the waist of the ship; picture someone lying down in the water. The waist is usually more of a structural term for the components at the ship’s main deck (which need not be at the exact middle of the ship; more on that further down).

I’m told the more contemporary term for the waist is the amidship, but since I am primarily interested in the vessels of yore I’ll continue to use the term “waist” where applicable.

Port and Starboard

When facing the bow (remember: the front), left is port and right is starboard.1

Useful mnemonic: if you’re on a cruise going from England to India and back, you want the P.O.S.H. cabins. Port Out, Starboard Home. The point is that you want cabins that have windows facing exotic Africa rather than boring, empty ocean, and therefore on the way out to India you want port (left) side viewing, whereas on the way home you want starboard (right).

And if that’s not good enough for you, here’s a classic earworm to help you remember, courtesy of Chitty Chitty, Bang Bang: “Port Out, Starboard Home, pooooosh with a capital P-O-S-H posh.”

Watch that video, remember the context of cruises from England to India, and you will never forget the difference. Also, did you know Ian Fleming wrote the book that movie’s based on? Like, Ian Fleming of James Bond fame. Crazy, right?

Bonus: the etymology of “starboard” comes from “steerboard,” because on Scandinavian longships the controller for the rudder was fixed to the starboard quarter (there’s that term for quarter: so starboard quarter would be the ship’s back right). Consequently, longships would always dock at the “port” on their left side so as to not pin the “steerboard.” In fact, an alternate and more archaic term for port is larboard. The term larboard was used for centuries, deriving from “lade board” as in the side of the ship on which cargo was laid aboard, or loaded.

This steerboard concept might seem a little strange, as we’re used to imagining the steering mechanism (the rudder) as being dead astern (at the exact stern, not quartered). However, in European ships, the steerboard steering mechanism was not moved to dead astern until the Age of Exploration, making for a design that still allowed for steering when the ship was heeling or listing.

We’ll get to heeling and listing a little further down.

Fore and Aft – Fo’c’sle and Sterncastle

These mean the same as bow and stern: fore is the front and aft is the back, easily remembered as what comes before and what comes after. In contrast to bow and stern, fore and aft are more about cardinal directions than structure. See figure above.

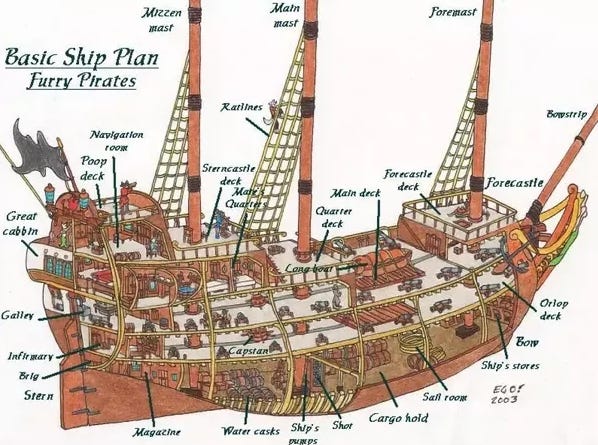

One place they do get used is when talking about the “castles,” raised decks at the front and back of ships.

The forecastle over time got worn into its more common term, fo’c’sle (pronounced “FOAK-sul”). In the Age of Sail this is often where the crew berthed (slept).2

On the opposite end you have the sterncastle, which is the fo’c’sle’s complement at the aft. You’ll find these on medieval European vessels such as cogs and carracks.

The sterncastle’s later iterations got reserved for the officers and their activities. As you can imagine, the sterncastle typically took less abuse than the fo’c’sle. Not to mention one lent itself to better accommodations than the other: the fo’c’sle got tapered into a triangle at the bow while most sterncastles got a more spacious layout given the transom (the flat-ish part of a ship’s stern). Would you like to live in the mostly square-shaped room (sterncastle), or the room shaped like a pizza slice that’s constantly getting hit with ocean spray (fo’c’sle)?

The “castle” part of this term was much more literal once upon a time. You can easily imagine raised and reinforced structures at fore and aft for archers. If you want to see some really cool and radical renderings of this castle-on-water concept, look up images of medieval Chinese warships.3

Decks

This next part should give you a good sense of a ship’s general cross-sections, based on the places where there’s stuff to stand on. And here you’re also going to quickly realize that almost everything on a ship is simultaneously linked to the rank and delegations of the crew. I’m saving the enormous subjects of crews for a later article, but you’ll certainly start to see overtures of it here.

Weather Decks

Ships can have different numbers of weather decks, which you can remember as decks that can get directly rained on. A deck is considered distinct from another when it’s at a separate elevation, much like a different floor in a building or stratum of rock. In order to cut through the confusion we’ll look at an extreme example of a five-decked ship. Know, however, that all of this applies to smaller vessels as well.

Moving from bow to stern (right to left on the image):

Forecastle deck

I have not seen this called the “fo’c’sle deck;” the unabbreviated form seems to get retained when it’s used as an adjective.

See also forecastle head, an additional mini-deck that on very large ships got stacked atop the fo’c’sle for handling the anchor — although on today’s naval ships the forecastle deck is often continuous with the main deck but raised forward. Take a look at a contemporary battleship and you’ll see what I mean.

Main deck

Strictly speaking (and this is important), the main deck is the only deck that runs the length of the ship and is at least partly exposed.

You could also say it’s the only flush deck (a deck that stretches stem to stern) that is also a weather deck.

You can see that in the image, and you can also see how the main deck is your access point to the lower decks, and naturally also had cargo hatches to the ‘tween and lower decks (more on those further down). Here we can also return to that term, the waist, and identify it more accurately as the part of the main deck that is roofless. In fact, in a few cases I saw this get called the waist deck, but for clarity I would stick with the term “main.”

Quarterdeck

Here we see “quarter” again begin used as an alternate term for the aft section. It appears the term quarterdeck was more used to denote function rather than level — the fuction being for officers and ceremonies. Indeed, on some ships the quarterdeck was part of the main deck; specifically, the part where officers did their thing.

In lieu of that, you might hear the quarterdeck simply get referred to as the poop deck, especially if there are no decks above it.

Sterncastle deck

Right where we would expect it, but in this case there’s a small structure, a navigation room, built onto the sterncastle deck, which is a logical place to put such a room considering its proximity to the wheel.

I’m told sterncastle is actually a medieval to early Renaissance term, and as ships began to prioritize aerodynamics in the 17th century the term fell out of usage and got assumed by the others: quarterdeck, poop deck, or deck house.

Poop deck

Coined to the utter delight of risible elementary schoolers everywhere. Some say it’s so named because birds would land here and leave their excrement, but that’s not actually true — it’s from Latin puppis, which means stern.

That said, based on its positioning above the navigation room, on certain iterations of ships it was probably little frequented, and therefore a fine enough place for avians to park and likely relieve themselves.

I will note that at least in the case of packet ships (19th century cargo ships), you had a fo’c’sle and main deck, and the poop deck was where the ship’s wheel was. If you’ve only got one raised deck at the back, then that deck appears to get the title of “poop” while “quarterdeck” and “sterncastle deck” get skipped.

Lower Decks: Lower, ‘Tween, Orlop

The deck below the main deck was called the lower deck. Sometimes there was another deck inbetween the main and lower deck called – wait for it – the ‘tween deck. The ‘tween deck could be for cargo or could be fitted with cubicles for berthing of steerage passengers, aka 19th century passengers flying economy, Spirit Airlines. As you’ll recall from our fo’c’sle vs. quarter discussion, the opposite of steerage passengers, the first-class accommodations, were called cabin-grade, and they stayed in the same vicinity as the officers and enjoyed access to food and entertainment.

You could also have a gun deck below that, which hosted the ship’s battery of cannons and was usually the flush deck that was closest to the waterline. In a really big beast like a ship-of-the-line you might have multiple gun decks, which would be designated by lower, middle, upper, etc. It’s worth noting that in smaller ships like frigates the gun deck was the same as the main deck — which simply means that the non-weather portion of the main deck (the part that had a roof) was where they arranged the cannons, which we might intuitively expect.

In many cases the gun deck could also be a crew quarter (especially when it occupied the same vicinity where one would find the fo’c’sle). The crew would sleep in hammocks slung between the cannons, and could even open the gun ports for fresh air. Not a cubic foot wasted.

The very lowest deck was called the orlop deck (from the Dutch for “overloop”). It was used primarily for storage. If the ship had a brig (a jail), it would be on the orlop deck toward the stern. The orlop also frequently got improvised into a field hospital since it typically sat below the water line, meaning it was safe from enemy cannonfire… as well as fresh air, unfortunately.

You could also have a hold under this. Storage purposes only, unless you’re a rat or rascally stowaway.

Bilge

There’s of course the lowest point of the ship where the keel is exposed (the keel is like the spine of the ship; if you’re unfamiliar, look up keelhauling and you won’t soon forget), and this odious kombucha trough is called the bilge.

The bilge is not considered a deck because it’s not a deck. You wouldn’t call an unfinished attic with exposed rafters a floor for the same reason unless you’re a US realtor circa 2021.

Ships have pumps to remove water, but you can probably appreciate that there will always be some liquid — often the heaviest and murkiest — that ends up in the bilge, sloshing back and forth in the darkness never to see the light of day. This accumulation of urine, feces, emesis, rats living and dead, and other such effluence is called bilgewater, and meant that all ships probably smelled awful below decks.

Note: I don’t mean all septic went to the bilge. Ships did have toilets at the bow and stern. But if for some reason you missed that toilet…

Enterprising as sailors were, even the bilge’s rank odor could serve a purpose. There’s a reason that sweet-smelling bilgewater was taken to be a bad omen: if your bilgewater smells sweet, you’ve probably sprung a bad leak!

Bilges also happen to be where American light beer is sourced from. The more you know!

While we’re on the topic of stenches, there was another odor on every ship: wood rot. Wooden ships were simply built thick enough to handle it, and would eventually be retired (except for the captains seeking to squeeze just a few more journeys out of them to their demise). The most structurally critical parts of a ship were often made with cedar, since cedar wood is resistant to wood rot, but most of the ship was made with oak and simply had an expiration date slapped on it. The process of inspecting these ships to determine their seaworthiness fell to insurance companies in the 19th century, but you can bet crews did everything they could to cover up any compromises in their vessels, the equivalent of a homeseller hastily bleaching a basement in hopes the inspector won’t notice the mold problem.4 This led to standards and inspection processes, and eventually to better quality and safer boats being used overall.

Now that we’ve covered the decks, let’s go aloft and check out the masts.

Masts

Fore, Main, Mizzen, and nth

In order from stem to stern, the masts are fore, main, and mizzen. If there are only two, then just use fore and main.

The only outlier term here is mizzen. The internet is hardly uniform when it comes to reporting the etymology, but it all seems to come from terms for “middle,” even though the mizzen mast from what I see seems to be the one closest to the stern. I’m told this had to do with four-masted ships like carracks, where you could expect a fourth mast abaft the mizzen sometimes called a Bonaventure mizzen.

If there are more masts than those three, the ones after the mizzen get increasingly sillier names that will never not make me giggle like a child. They sound like reindeers who didn’t make Santa’s draft:

Full disclosure: this diagram is a little misleading. Several of these names more readily belong to sails than masts, though you can probably appreciate how one category lends itself to the other.

Jigger: this could refer to a fourth mast (like the aforementioned Bonaventure mizzen), or to a small mizzenmast sail (again, saving sails for next week).

Driver: again, this typically refers to a sail (a gaff sail, to be exact), but I’ve seen some resources identify it as a mast, so I’m putting it here; it could actually be abaft the spanker.

Pusher: kind of rare term; like the driver, this one could also be abaft the spanker.

Spanker: without question the naughtiest mast — romance writers, make it so! That said, I’ve frequently seen spanker either refer to:

the fourth mast on a four-(or more) masted ship (fore, main, mizzen, spanker)

a sail (commonly fore-to-aft and gaff-rigged; terms that will make a lot more sense later on) connected to the mizzenmast that functions effectively as a wind rudder

It’s also worth noting that any ship with more than three masts is going to be an absolute leviathan — see the Thomas W. Lawson, launched in 1902 and wrecked in 1907, the largest non-motorized sailing vessel ever built.5 Additionally, any masts abaft the mizzen might just get boring ordinal names, especially on their blueprints which have to be translated by non-sailors (fourth mast, fifth mast, sixth mast…).

You can always depend on the first three though: fore, main, mizzen. Or, in the case of just two, fore and main.

Maneuvering

Headwind and Tailwind, Tacking and Jibing / Gybing

Tacking

You’re on a sailing ship. If you’re lucky, the wind is at your back. This is called a tailwind, and one might say you’re “running before the wind.” Great!

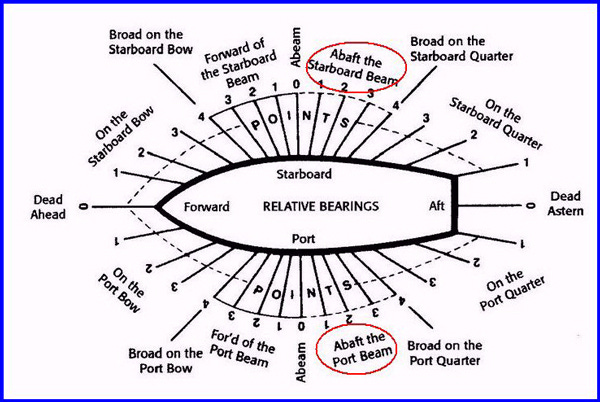

If you’re unlucky, you’ll be facing a headwind, where you’re pointing at your destination with the wind in your face. Ships cannot sail directly into the wind. What now?

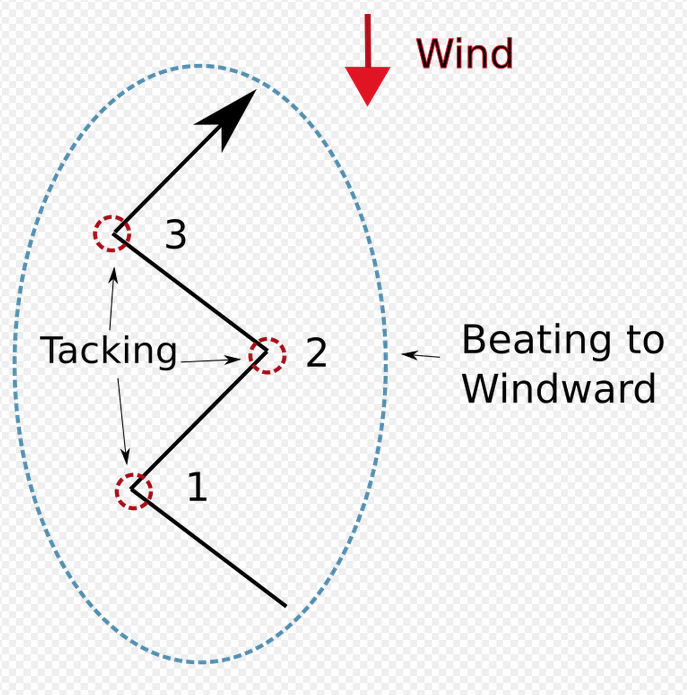

Well, you can still get to your destination, but you’ll have to beat your way there using tacking.

Beating is where you steer in a zigzag fashion, allowing the wind to blow angularly across your sail — in the same way an airfoil generates lift — and propel you forward in slices. Beating is the name of the whole operation, i.e. “beating to windward.”

Tacking refers to the motion of turning the ship at each “corner” of the zigzag. Specifically, it’s turning your ship into the wind until it’s blowing angularly at the other side.

Caveat: I sometimes see tacking refer merely to heading windward at an angle. It seems this is the case when one speaks of being on a “port tack” or a “starboard tack.” It appears as though when one is tacking (the verb) then that refers to the maneuver of turning into the wind, whereas port tack and starboard tack (the nouns) refer to the side from which the wind is angularly approaching.

In the figure below, the numbers 1, 2, and 3 designate where the ship must execute a tack. But the segment between 1 and 2 would be described as “sailing at a port tack” because the wind is hitting the ship’s portside, while the segment between 2 and 3 denotes a starboard tack.

You can surmise that you want to limit the exposed face of your sails as much as possible during the tack maneuver (minimize drag) in order to reduce the amount your ship is driven back. There’s a moment in the tack when your sails will be exactly perpendicular to the wind and will luff (go limp) which is when your craft is vulnerable to being pushed back. A tack has to be quick and intentional, and have enough momentum behind it to make that turn and catch the wind again on the other side.

As someone who’s had a half-thimble’s worth of experience doing this, I can tell you it’s truly exhilerating.

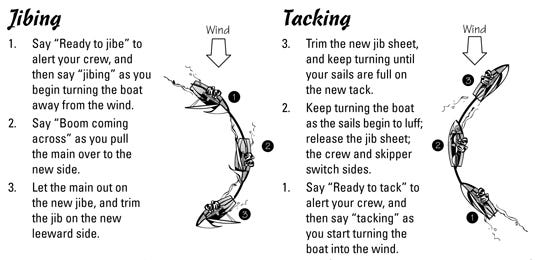

Jibing / Gybing

The opposite of tacking is jibing (also spelled gybing), and is the same maneuver executed during a tailwind (beating to leeward).

Jibing can actually be more dangerous than tacking because of the strain put on the ship’s structure, and if your sail’s rigging has a boom then that boom is going to go rocketing above the deck and could take an unsuspecting crewman with it!

Pirates of the Caribbean is not exactly a credible authority on seafaring, but there is a scene in the first movie where Jack Sparrow executes a jibe to leave Will Turner dangling over the ocean by the spanker’s boom during a tense negotiation aboard The Interceptor. An honest man would have shouted, “Helm to lee!” or “Boom’s coming over!” But not Jack Sparrow… ahem, Captain Jack Sparrow.6

Heeling and Listing, Weather and Leeward

This is pretty straightforward. When a ship begins to tilt7 to one side due to an effect like crosswinds (like what you get during tacking maneuvers), this is called heeling. Shipwrights actually sometimes designed sails precisely for heeling, a phenomenon you can see in modern racing sailboats.

Heeling is similar to but nonetheless distinct from listing.

Listing refers specifically to an issue on the ship causing it to tilt one way or another, whereas heeling is meant to be something that the ship will naturally correct. If a ship is heeling due to wind, then once the wind abates the ship will correct itself. In contrast, if the ship is overloaded on the portside and the whole craft is bent that way, then you have yourself a portside list. It’s not a heel because, if left alone, the ship will never stand up straight.

I kind of blew past this point (badum, tss), but let me say it explicitly here: windward or weather is the side of the ship taking the wind head-on, and leeward is the opposite. So if the wind is hitting the portside and departing on the starboard such as during a port tack, then the port is windward and the starboard is leeward — if the wind is particularly strong then your ship might be starboard heeling.

This was critical for the crew to keep in mind. During high winds when sailors ascended the ratlines (the rope nets running from the edges of the decks up the masts), they were always taught to climb up on the weather side so the elements were pushing them into the ropes, rather than the leeward side where nature would be working to rip them off and into the ocean. Worse still, if the ship heeled they would find themselves overhanging the water!

This general practice actually became a problem for the crew and immigrant passengers of the Powhatan in 1854. The Powhatan’s portside struck the New Jersey shoals during an April nor’easter (a general name for the awful early spring storms which are periodically visited upon America’s northeast, ergo “nor’easter”). Crew and passengers alike clambered up the weather side ratlines which happened to be on the portside. Then the waves pushed the craft until it listed in that direction and had all the survivors dangling over the whitecaps. Over the course of hours survivors succumbed to exhaustion or hypothermia and fell one-by-one into the ocean. Every single one perished within sight of land. That disaster spurred the government to fund wreckers, men who lived along the shore and were equipped to respond to nearby wrecks.

Ask me more about this sometime, because it’s actually a super cool topic but we need to stay on track.

Structural Considerations

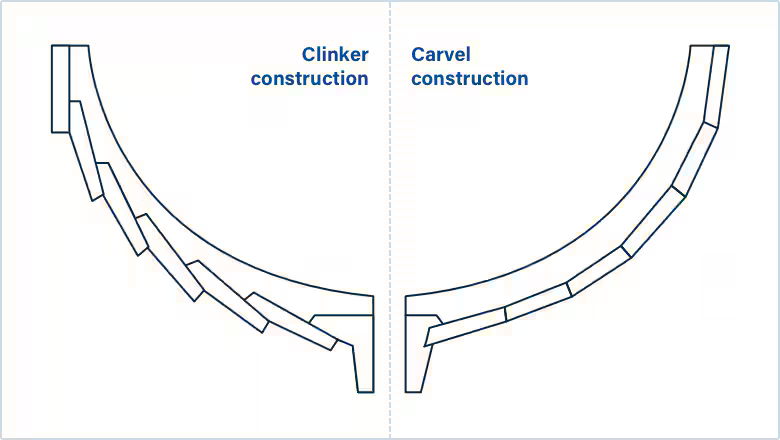

Clinker versus Carvel

This section is a little bit of a non-sequitur, having more to do with the history of shipwrighting. I don’t really know where else to put it and I think it’s valuable to know, so I’m gonna shoehorn it in right here. This is about how hulls are made.

If we look at Europe alone, two different traditions of hull design emerged: one in the Mediterranean and the other in Scandinavia.

The Scandinavian design was clinker-built, also called lapstrake, where the hull planks overlap. It’s very distinctive, and one of the things that gives viking ships their unique aesthetic.

The Mediterranean design was carvel-built, which is what all ships are today: a smooth hull, planks laid right up against one another.

To make this simple, here’s a side-by-side comparison:

Clinker advantages:

Construction doesn’t require saws (which are hard to produce); you can get by with an adze (basically an ax)

Hull planking is overall stronger, which means you can afford lighter framing

Better joints

Less caulking

Flexile; planks can “breathe” under load without admitting much leakage

Clinker disadvantages (just two, but they’re huge):

As clinker hull lengths increase, joining problems make this an impractical choice (one source suggests it becomes an issue at as short as 100ft spans)

You can’t cut gun ports into clinkers; if you want cannons not on weather decks, then clinker won’t do8

Carvel advantages:

Make the hull as long as you want

Guns go kaboom

Carvel disadvantages:

Saw required to turn out the square-cut planks

Requires a strong (read: heavy) inside frame

More caulking

Very difficult to get all those planks watertight; be prepared for constant seam maintenance and pumping out the bilge far more often

Going back to the question of framing versus planking, you can almost conceive of a clinker as planking with a supporting frame, while a carvel is framing with planks. Clinkers are built shell-first, then frames added. Carvels are built around a frame.

It’s also pretty easy to see how, on a tight budget or lower tech, clinker was the way to go. That changed when the demand for larger, longer ships started to rise. That said, longboats all the way into the 20th century still used clinker designs due to the reasons listed above. Pick the best tool for the situation.

Hogging and Sagging

Back to ship dynamics for a minute. This one I think is super cool.

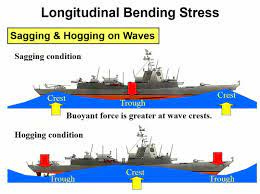

In nautical engineering, ships are affected by cyclical stresses from oncoming waves. If you imagine the length of a ship as a fixed beam, the waves it encounters will make it rise and fall following the waves’ crests. The weight of the ship combined with the constant movement of waves produces hogging and sagging.

As you can see, hogging occurs when the crest of the wave is near the center of the ship, and therefore the weights at the extremes (the bow and stern) force the ship into a concave shape. A few seconds later, the wave will have moved to the end of the ship and been replaced by another approaching one. Now the center of the ship is in the wave’s trough, and experiences sagging.

When hogging occurs, the top of the ship ends up in tension while the hull is in compression. In sagging, the decks are in compression while the keel is in tension.

This type of stressing and the deflections in creates are exactly why steel I-beams are so shaped, but this isn’t just static stress, this is cyclical. Cyclical stress is a heavily researched field of structural engineering, but even today is often computed empirically (albeit in computer models) for structures like vehicle shocks, roller coasters, elevators, etc.

Shipwrights in the olden days were constantly looking for ways of improving their vessels, getting a little more speed or stability out of them, especially when trade was firmly established across the Atlantic and dexterity and adaptation took a back seat to speed and efficiency.

By the way, I think it’s cool that this process of adding a little to length or thickness, removing structural components at the waist or strengthening in another area… all of this contributed to an intangible quality sailors referred to as a ship’s tenderness, having to do with how it sailed, its speed, how it heeled… basically its overall handling. It turns out that once you reach these minutiae, building a ship can be like fashioning an instrument.

It was common to hear captains speak this way of their craft in olden days, both positively and negatively — Columbus was reportedly not fond of the flagship he was lent by the Spanish monarchy, the Santa Maria. He thought it a somewhat crude vessel; stiff, where stiffness means the opposite of tenderness. You might think that’s the reason Columbus crashed it, but it’s not — he left it in the care of a young and inexperienced helmsman so he could catch a moment’s rest, and a moment is exactly how long it took the bufoon to total it. I’m sure there are parents reading this who can relate. I leave you alone for five seconds…

Alright, now that we’ve got our feet wet, let’s move on to discussing the lungs of ancient ships: sails and rigging!

And of course, be sure to subscribe:

You can also check out some of my fiction, which is my true bread and butter, and see some of these nautical terms at work:

Wyrmslayer

On the day the hunters arrived, the green ocean turned and the clouds drew lower until the isle’s mountainous peaks vanished about the gray curtain. Beads of chill rain ornamented the dark conifers among the basalt cliffs and promontories birthed by the volcano long ago. The month was Ecchinus and the summer constel…

Modern parlance dictates “left rudder” (port) and “right rudder” (starboard).

This term, berthing, also got used to denote how much space a a ship needed in order to make port (parallel park at the harbor). You can also see how we got the expression “give wide berth” from it.

…But before you try and use Chinese ship design in your fiction, probably read my section on sails first. There are reasons related to weather and navigation that the Chinese were able to build and utilize ships that look like buoyed castles while other regions were not. Such a ship would not do well in the Mediterranean.

This isn’t to say that all captains were conniving swindlers. When it came to combating wood rot, there simply weren’t many options. Craft preservation rapidly becomes a Red Queen’s race — even today, the modern US Navy has a multi-billion dollar division dedicated solely to evaluating and handling fleet corrosion.

This is a good example of a ship where the driver mast and pusher mast were recorded as abaft the spankermast.

Someone asked about this, so to clarify: the Age of Exploration / Sail ship’s wheel does not control the direction of the mast. It controls the rudder. Masts are very heavy, and structurally must be fixed to the frame in order to manage internal stresses induced by the sails (moment, or torque). Jack turning the wheel could have feasibly caused The Interceptor to jibe, which would have sent the gaff spanker sail across the poop deck (poop deck because there are no other aft decks to assume the other names), and the boom could have struck Will Turner. In short, the wind moved the spanker sail, not the wheel.

Here might be a valuable distinction: in nautical terms, pitching is the complement to heeling. Pitching refers to bow-stern tilting, whereas heeling is port-starboard tilting.

Extremely grateful to Brendan Foley for pointing this out.

Great writeup. I consider myself more knowledgeable than most, but am still petrified of mistakes (I know I've made more than a few) when writing anything involving ships. It's one of these areas where you just don't know what you don't know.

Great first post and I'm looking forward to the continuation. Ditto what B.A. Clarke said re: you don't know what you don't know.