Worldbuilding Guide: Nautical Pt. 2 - Sails & Rigs

All that cloth stuff.

Note: this subject matter requires some images and figures which increase the email size. For best experience, open this article in your browser or the Substack app.

Here we are at Part 2 of our worldbuilding and fiction guide. If you missed the first part, it’s advisable to start there.

Here in Part 2, we’ll be discussing sails and the terminology of their rigs (sail plans).

As you read this, a theme I’d like you to keep in mind is purpose. In the present era it’s easy to think of newer technology coming along and simply replacing the old stuff, like how the iPhone replaces the iPod which replaces the CD. With sail rigging, it’s more about the purpose of that particular craft. Whether it’s for warfare, smuggling, fishing, or racing, you’ll want to choose the rigging that best accommodates that purpose.

Lastly, a sailing ship is often defined by its rigging — brigantines, schooners, full-rigged. There are too many different types of riggings across too many eras and civilizations for me to glossarize all of them. Instead, I’ve opted to point out ones as we go and as they become relevant. I’m hoping this will make the learning process more organic rather than mechanical.

I feel a wind at our back — let’s run before it!

Sails

Square versus Triangular

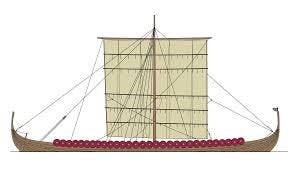

I want to kick off with this distinction, because I think it’s a highly misunderstood one and often abused. Scandinavian longships used square sails, as did Chinese junk ships (if not perfectly square in shape and structure, then mostly square in function, which I’ll explain). What’s up with triangular?

Going back to my severely and regrettably limited experience in real-time sailing on some Pennsylvania lake, I can at least report that this particular lesson is much more intuitively understood with a pinch of hands-on operations. But here goes…

Square Sail Geometry

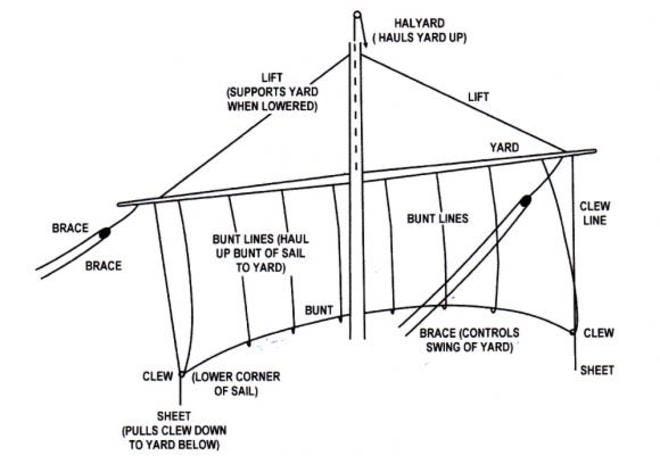

Square sails hang from a horizontal piece called a yard or yardarm that is fixed to the mast. Its orientation can be controlled by use of the braces — lines used to adjust the yard’s angle (see below) — but you can probably picture how its full range of motion would be pretty limited. The yard can’t rotate far without all the rigging getting tangled, and the mast probably isn’t designed to handle stresses in that direction anyway, and even if it did then you’re in for some aggressive heeling.

Triangular Sail Geometry

Triangular sails can handle headwind much better. While a square sail can only manage about 67°off windward, a triangular sail can handle 55°. That might not sound like much, but it’s actually an enormous advantage when multiplied by hundreds or thousands of miles, not to mention precision of maneuvering, i.e. tacking and jibing.

By the way, sailing as close to the wind as one can without being driven back is called sailing close-hauled. So to put things more accurately, quare sails can close-haul at 67°off windward, while triangular sails can sail close-haul at 55°.

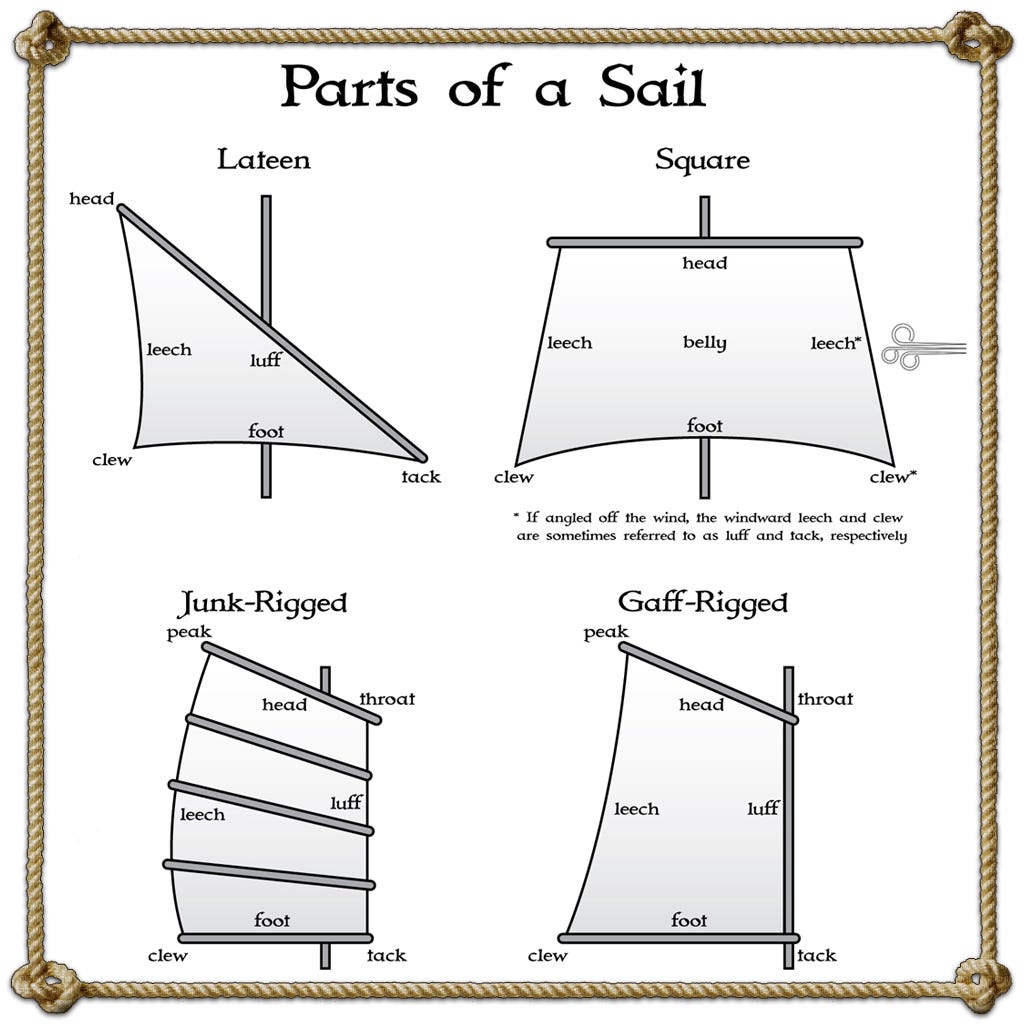

Triangular sails require three points of contact. These three points are the head, tack, and clew.

As far as which is which, the head is easy enough: it’s at the top. The tack and clew are a little more complicated, so refer to the ship above and follow along:

The tack is always the lower forward corner of the sail.

The clew is always aft.

Technically, the corners of square sails are both referred to as clews. Square sails have no tack since both corners serve the same fuction, ergo they are both clews. The exception to this is if one corner is positioned afore the other; in that case the forward corner is called the tack and the aft corner is the clew. As we saw last week, lots of nautical terms get reused in ways that follow intuitive patterns.

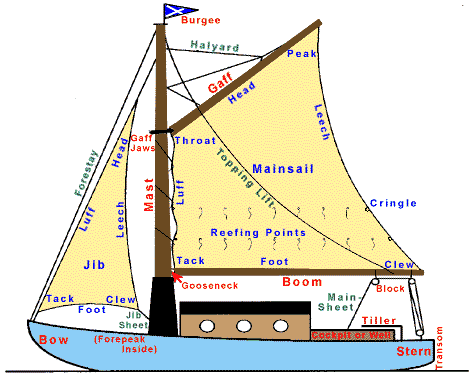

In terms of the sides or edges of the sail (as opposed to the corners), the terms are head, foot, leech, and luff. You can see the same figure above for that:

Head and foot are just top and bottom.

The luff is alway fore and the leech is always aft. If they’re parallel as in your standard square sail, then both edges are called the leech. You see the pattern: the leech is to the clew what the luff is to the tack. If you remember that, you’ll remember the rest. They even touch one another. Again, check the chart above and you’ll see what I mean.

This head-tack-clew term even applies to lateen sails (see figure above left), which are sort of a hybrid sail as the triangular sail is fixed to a yardarm. In this case, the head is the high end of the yardarm, the tack is the bottom corner still fixed to the yard, and the clew is the free side. Actually, lateens are some of the oldest sail rigs ever since they’re highly versatile and quite easy to use.

Basic principle of drag: the thrust (i.e. speed) one extracts from the wind is directly proportional to the cross-section of exposed sail. Therefore, square sails generally produce more thrust, i.e. they’re faster. The point of a triangular sail is that you are trading some of that surface area (speed) for maneuvering and adaptability that you couldn’t as easily get from a square-sailed craft.

You see this in cases like the aforementioned longships and junk ships. Scandinavian longships needed large crews to operate the oars when winds were unfavorable, and they’d be ordered into the thwarts (the stalls running to either side of the decking with benches for handling the oars) to manually propel their craft.1

By the way, this is probably an important point as to how vikings gained naval superiority along the entire European coastline and any rivers and tributaries unfortunate enough to empty thereupon for around four centuries. Much is said about their innovative ship design and techniques, but they also simply had moxy to hop into their thwarts and start rowing when the seas got high or the rivers narrow.

Differing Usage

Junk ships worked for the Chinese because China has massive lakes with very regular weather patterns which they could easily negotiate with their square sails to great effect. They had no need of triangular sails.

Once Europeans started to explore the Atlantic beginning in the 16th century, they needed new ways to handle those fickle weather patterns, as well as enemy ships from opposing nations! And to drive the point home, once exploration and colonialism cooled and regular Atlantic trade routes came into effect in the 19th century, crews were incentivized to return to faster and less finessed crafts to purvey their goods as swiftly as possible. Ergo, you got clippers and packet ships2 with these enormous square sails that did their jobs well… until storms started wrecking them because they’d sacrificed maneuverability for speed.

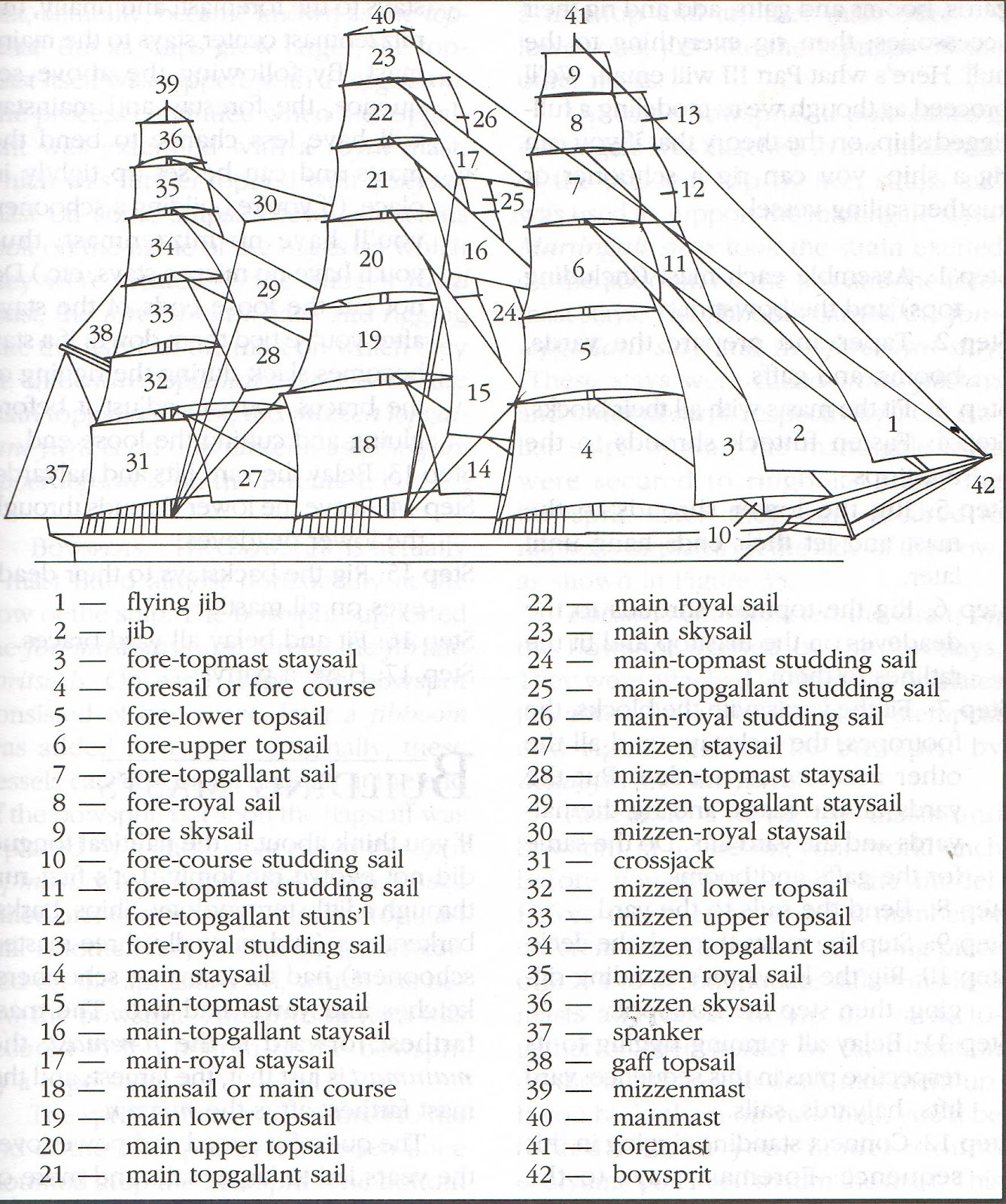

What you see above is a typical packet ship. On fore-, main-, and mizzenmasts, the number of square sails per mast you’ve got is 5-5-4 and four jibs at the bowsprit (jibs are the fore-and-aft triangular sails). Compare that to a “Golden Age of Piracy” ship-of-the-line, the largest class of that era, which was 4-4-3 with only three jibs. A packet ship simply had more surface area in terms of canvas, and could have generated significantly more thrust.

I do want to add a word of caution here lest I be accused of historical reductionism… speed versus handling was not the only factors in the evolution of ships through this period. Packet ships could and did certainly use tacking techniques across the Atlantic (they had to in order to reach New York from Europe), and many of these massive ships did so to great effect. My point is that the demands of the eras shaped the usage of sails, and their evolution bears out the general applications of square versus triangular sails. Packet ships were rigged for maximizing cargo transport. Ships-of-the-line were rigged for war.

Square Rigging Names

The names of the square, mast-mounted sails are fairly straightforward. I’ll lay them all out in the most extreme case of a windjammer (sailing rigs with profuse endowments of sail — the term came about right when steam power was becoming the next big thing, so was originally a pejorative), then explain them a little better below: from bottom to top: [mast]sail / course, (lower/upper) top-, topgallant-, royal-, and skysail.

I know that sounds confusing, but refer to the figure then look at my breakdown and formula:

If you’re starting from the deck and working your way up to the halyard, it’s like this, with formula followed by example:

[mast]sail or [mast] course – mizzensail or mizzen course

[mast] [if required, lower/upper] topsail – fore-upper topsail

[mast] topgallant sail – mizzen topgallant sail

[mast] royal sail – main-royal sail

[mast] skysail – fore skysail

Triangular Rigging Names

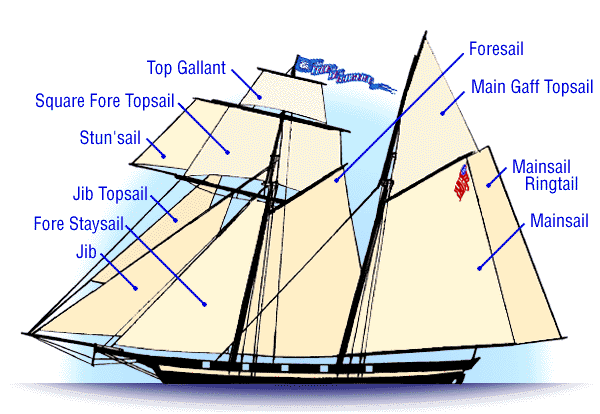

I’ll try and keep this simple. In general, if you’ve got a bunch of masts and square sails like we’ve been discussing so far, the triangular foresails connecting at the bowsprit are jibs, and aft jibs / gaffs are often spankers (unless the ship has a ton of masts and one of the masts is referred to as a spanker). For example, the figure below is for a two-masted schooner, a design dating back possibly to the 17th century. You can see that the jibs get complex, but the names of the masts and primary square sails are all present and where you would expect them to be:

Minor caveat that many schooners had no square sails at all. The fact that this one does though makes it a great example for learning the nomenclature. Schooner rigs were used for a variety of purposes: privateers, blockade runners, slave and fruit ships (read: “cargo” subject to rapid expiration in transit)... all purposes requiring both speed and dexterity. These were used all the way into the mid-20th century.

I know I haven’t gone over jibs, but I’m saving that for the fore-and-aft section further below.

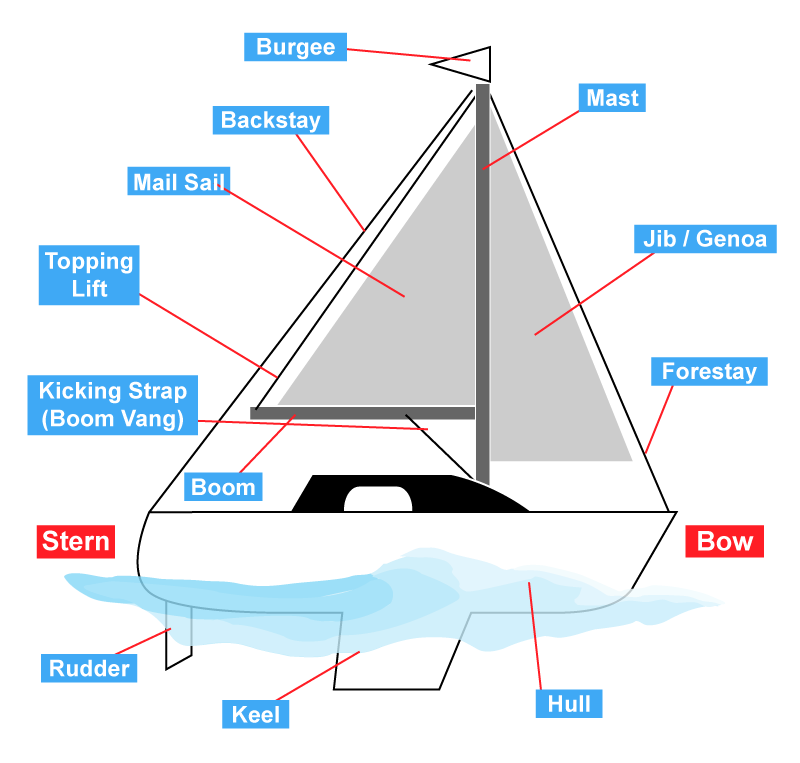

To my previous point, you can see there’s a whole lot of canvas on that thing, but even the mainsails are connected on top and bottom to something akin to yardarms, although in this case we call the bottom a boom and the top a gaff, hence the term gaff-rigged, a word you can see reflected on the figure’s main gaff topsail. You can check out the “Parts of a Sail” diagram above for a reminder.

You’ll notice too that some of the hierarchy governing the square mast sails makes its way into the other categories, like how the smaller triangular sail above and mirroring the jib is called the jib topsail.

Consider the figure below of a broads yacht. I include this figure because it has a bunch of the terms we’ve learned, so use it for reinforcement of concepts. You can also see how frequently on these smaller crafts the mainsail was gaff-rigged. These would be some seriously nimble ships.

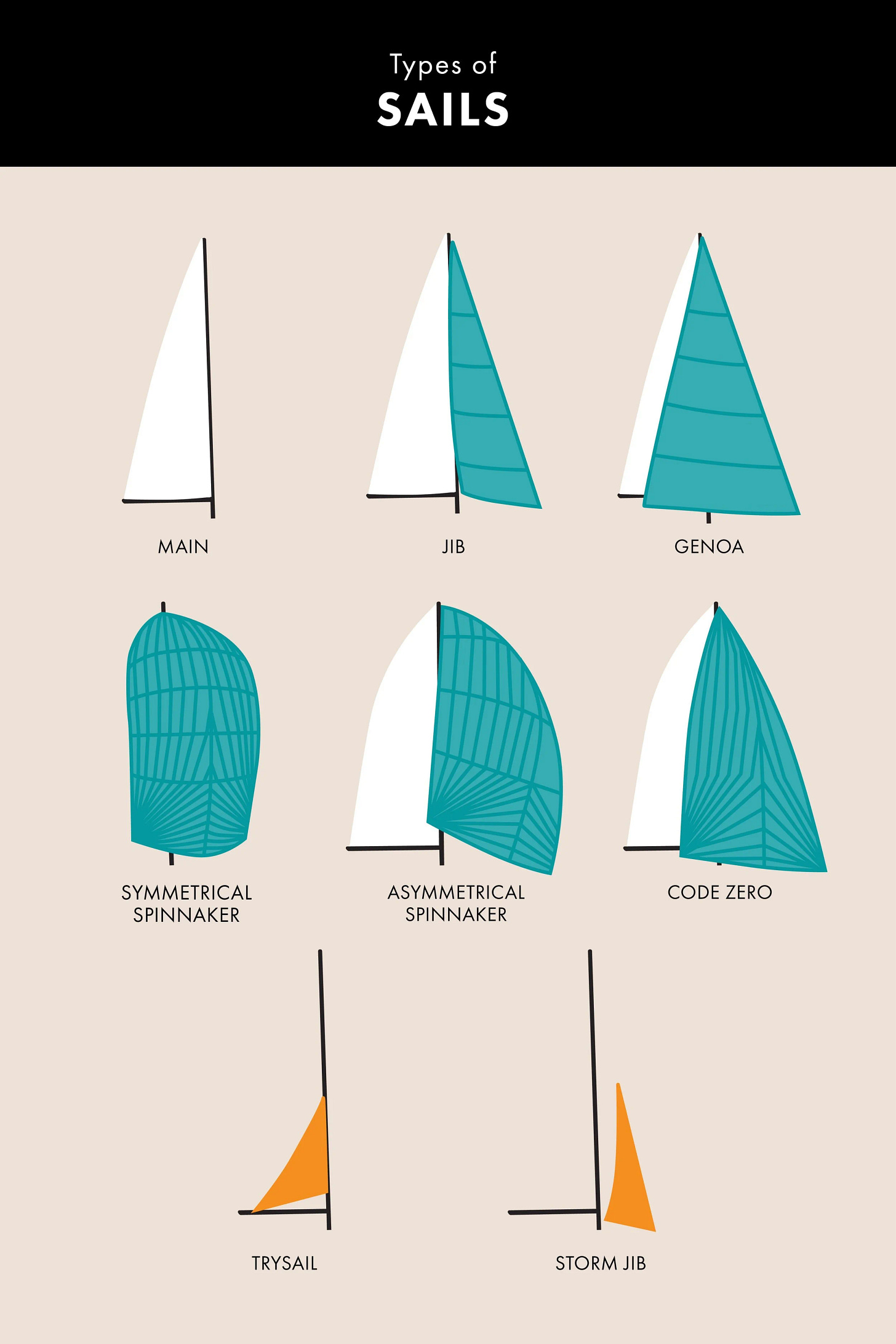

Most modern yachts like the ones you’d see in a child’s drawing are called Bermuda or Marconi rigs.3 Bermuda rigs have two triangular sails: the aft sail attached to a boom is called the mainsail, and the foresail strung to the bow is the jib.

It’s all exactly as you would expect, the only nuance being that a jib that extends at least partly abaft the mast with potential to overlap the mainsail is often called a genoa. In fact, genoas are often designated by their percentage of overlap (115%, 150%, etc.). When the term genoa is used, it’s usually in lieu of calling it a jib. See the figure below distinguishing jib and genoa, along with some extra terms:

Bonus term: a boom’s pivot-point on the mast is known as the gooseneck. It’s not only there to rotate, but to move vertically to better control the shape of the sail.

It’s also interesting to note that on a Bermuda rig the head of both sails is fixed very high up the mast, which under strong winds is going to generate a lot of internal stress. The Bermuda rig’s popularity rose with the advent of tougher materials like aluminum and fiberglass to replace wooden masts — not feasible for big ships, but great for the likes of small, private yachts. A little bit of technological growth, but still purpose.

Now that we’ve covered this, you can go back and look at our two archetypal examples of square-sailed ships, the longship and the junk. You’ll notice neither one has a bowsprit, because bowsprits are for jibs. They have prows, but there would be nowhere to tie off a jib tack even if you had one.

This is a common mistake made in fantasy renderings: we’re so accustomed to sailing ships having stems that we even put them where they’re not needed. The exception is when the stem is not a bowsprit, but a ram as in the case of a trireme. I said this in Part 1, but it bears repeating: rams are a very different structure for a vastly different purpose — their job is not to support rigging, but to punch holes in enemy hulls. I won’t elaborate on this here because this section is about sails.

Fore-and-Aft Sails

While there’s evidence of fore-and-aft riggings being used by the Austronesians as early as 1500 B.C., it took much longer for Europeans to begin using the same. That said, considering what we’ve already learned of sail functions, you can probably appreciate that fore-and-aft sails are pretty complex and sensitive instruments. Managing them would require a knowledgeable and disciplined crew.4 Remember: purpose.

Jibs

This is pretty simple, and you might have already caught the pattern. If there are multiple (typically you’ll find multiple at the bow) then from outer to inner it goes like this:

Flying jib

Outer jib (if your rig only has two jibs, this name gets dropped)

Inner jib

You can also have a jib called a staysail (usually called a fore staysail given it’s fixed to the foremast, see figure above), but its position can vary depending on where on the mast it’s fixed to. Staysails also need not be at the bow — sometimes they’re set between masts.

Aft Rigging

Typically these are called spankers, and are often gaff-rigged, but they can also be called jiggers, drivers, or even (colloquially) pushers — names that should be familiar from our prior discussion on masts. In the right-hand side of the image below, observe the gaff-rigged sail protruding out past the transom (the generally flat part of the ship’s stern) — that’s a spanker.

Note that a spanker need not be gaff-rigged. The obvious advantage to gaff-rigging is that it gives you an air rudder, but the disadvantage is that it’s more difficult to furl and can generate a force vector that is unaligned with the ship’s center of mass — if it’s catching wind, it could be turning the ship. A gaff-rigged spanker will make a ship highly mobile, but as with all choices that comes at a price.

It’s also interesting to me that only the topsails are unfurled on each of the masts. This is an image of the U.S.S. Constitution heavy frigate, aka “Old Ironsides,” the world’s oldest commissioned naval warship still afloat, and if you recall the section on ship’s structuring you’ll know that’s a remarkable feat. She’s undergone multiple restorations, but still floats with her original keel!

Look at the size of that bowsprit… aren’t sailing ships beautiful things?

And that’s all for this week! Next week, we’ll take on navigation, including the various tools and techniques sailors would use to get around. Subscribe to get it right into your inbox!

Also, while I love these research and study pieces, my true passion is my fiction. Check out the story below where I put some of these sailing principles to work:

The Myr Has a Thousand Eyes

Late spring — by rosy evening light the barge rounded the bend in the marsh. A steady northwesterly breeze touched the lateen sail with its yard bent diagonally across the barge’s fifty foot length and single cabin at its center. On every bank the golden stalks of berse swayed and feathered while a few copses of pine and…

This isn’t just due to the absence of triangular sails. In some cases like narrow rivers, sailing upstream is prohibitive.

Minor addendum: “packet” and similar terms refer to a ship’s role, not its rigging. Case in point, the term clipper survives to the present day.

I’m told that Marconi rigs can be slightly different than Bermuda rigs. Marconis identify tall masts and high aspect ratio sails. Bermudas are the specfic triangular sails. In practice though, they’re the same.

Not that square-rigged sails were simplistic tools requiring no specialization; this is merely to say that adding fore-and-aft introuduces a whole new dimension to sail management that comes with its own demands.

Fascinating.

It should be noted that packet ships often fell prey to three masted warships, because for all their speed, the triangular shaped sails let the ship travel closer to the wind and gained that speed. That and they could put out more studding sails. Three masted frigates always invariably caught up to the packet ships.