Nitpicking Worldbuilding: That Darned Wagon

Fussy fantasy questions can lead to better storytelling.

I’m not big into zealously tearing apart mainstream media franchises… but here we go.

Okay real talk: I know Amazon’s Rings of Power gets a lot of flack for many different reasons and I’m not one to add to the noise.

With that said…

This might not have been the image you’d think would trigger me, but I immediately hit the pause button and gave Mrs Dunmore a lecture she probably didn’t appreciate.

Can you guess what my issue was?

Why so Ornery?

Before I go any further, I want to be clear about what this kind of criticism is for and isn’t for.

It’s not for tallying up inaccuracies like an episode of CinemaSins. I’ve said this before on occasion, but let me say it again with all trenchancy:

The point of applying historical pedantry to fantasy isn’t to force storyworlds to become real-life simulacra (or simulacra of anything else, for that matter). If that were the goal, then we should all quit writing fantasy and switch to writing historical textbooks. The point is and always has been to make the stories better!

If ever the lens of historical accuracy depreciates a story’s value then that lens has outlived its usefulness and ought to be discarded.

Acknowledging that, however, one of the biggest obstacles facing widespread acceptance of the fantasy genre is precisely its believability. As it turns out, realism can have an immense influence on that whether the audience is conscious of it or not.

I know people who adore Star Wars or will gush over works of magical realism… but who will directly tell you that they’ll never read or otherwise consume fantasy. It’s just beyond the pale for many people, and I believe a large part of that is because of moments like that wagon we just looked at.

Don’t worry, I’ll explain why in a moment.

A Note on Realism

I already touched on this, but in this genre, realism is not a goal in and of itself. Plenty of distinguished writers would rather have fantasy that overflows with unfettered whimsy and where only the boldest of dreamers may tread.

That is totally valid!

There are excellent fantasy stories that harness just such energy. I will never turn my nose up at Miyazaki.1

But I will propose a rule of thumb:

Digressions from historical or literal realism typically work better when they are intentional rather than accidental.

Personally, I would be willing to bet that the digressions from reality depicted in Rings of Power’s wagon were not intentional, and are to the show’s detriment.

Whether or not you immediately perceived what was wrong with the image above, I nonetheless submit that a small application of historical knowledge on the part of the writers and directors could have made that whole scene much better. More believable and credible. Better storytelling.

Before I continue, SPOILER FOR RINGS OF POWER SEASON 1. IF YOU DON’T WANT RoP:S1 SPOILED, SKIP THIS ARTICLE COMPLETELY.

The Wagon Scene

Once again I want to say that Rings of Power has been raked over the coals many times over and I’m not here to flippantly revel in the hate. That said, I’ll be uncapping the ol’ red ink pen.

First, let’s run through the events, which you can watch yourself on YouTube here, but I’ll outline:

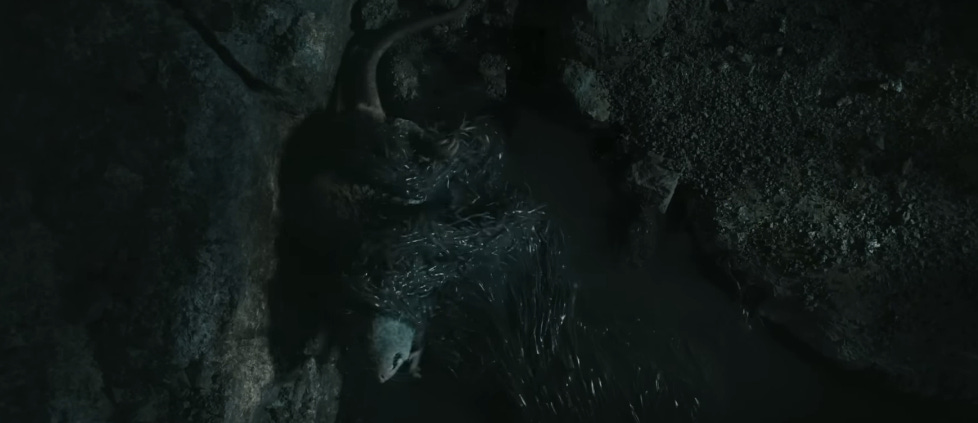

The sequence is a flashback of when Sauron (the big bad Dark Lord) fell from power. His disgruntled minions slew him in his own throne room, but his gooey essence escaped through the cracks in the floor and recongealed deep underground. There he turned into Marvel’s Venom and munched on rats and centipedes and other unappetizing content… still better than a salad though.

When he’d gained enough XP consuming low-level critters in this starting zone, he ventured out into the open world and found his way to a lonely path where a hapless woman was driving a cart.

He managed to latch onto the cart, lurched his way to the driver’s seat, and ate the woman. The horse became frightened by this and… unhitched… itself? From the? Wagon?...

How?...

And with the woman devoured, Sauron had finally acquired enough XP to level up from the Venom form into the Human form.

End scene.

Okay now I know I related that with more than the daily recommended serving of snark, but truth be told everything in that sequence was serviceable! Besides the horse, there weren’t any gaping plotholes or irregularities.

But that wagon…

Do you see what I see?

It’s the Wheels.

Look at it again.

What follows is a brief lecture on wheel design… I know that might sound boring, but I promise I’ll make it worth your while.

Indeed, the whole point of this essay is that fussing over details like a stupid wheel can bolster the quality of your fantasy story at compounding interest rates.

In the end, it’s not about the wheel. It’s about the story, and these stories can be greatly enhanced simply by educating oneself and asking very pointed and persnickety questions about minutiae like wheels!

Like a Wagon Wheel

We’ve been conditioned to think of non-industrially-produced objects as being simpler or easier to manufacture than the goods we use today. This is an unfortunate modern fallacy — it’s more accurate to say that simple(r) technologies of the past were often optimized to old uses, manufacturing techniques, and resource availability.

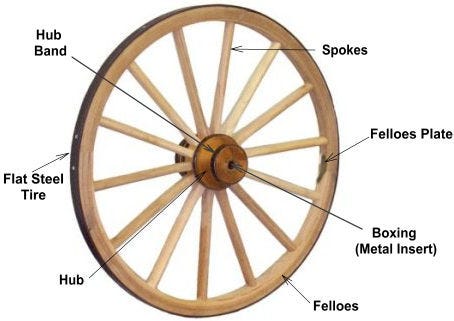

Nothing on a cart gets more abuse than the wheels. They’re subject to unreal degrees of cyclical stress. This is why wagon wheels were spoked rather than solid: besides being lighter, a spoke can counterintuitively manage compressive and tensile forces better than a solid piece of wood.

And lest the point be missed, spokes were invented around 2000 BC, while the wheel itself was first developed around 4000 BC. Let that sink in: for two-thirds of the entire time that humans have been using wheels, we have also been using spokes. By the time a distinct alphabet emerged from hieroglyphics, we’d had spokes for a couple hundred years.

I could go into far more details on the value of spokes,2 but I don’t need to. Suffice to say, if we’re still using them four-thousand years later, they’re a pretty good design.

But even an unspoked, solid wooden wheel would work better than what Rings of Power has! Theirs is made of wood planks, which means it has seams!

If I asked you intuitively to guess where and how you might expect these wheels to fracture, you’d probably guess along those seams.

And you’d be exactly right.

Even if this wheel weren’t obviously made from planks and were instead cut from a solid piece, it would only avoid this critical flaw if the pieces were cut laterally from an improbably round treetrunk! Any standard cut would introduce the same sort of faults along the wood grain!

I’m aware that if one googles “medieval cart wheel” or “medieval cart” one will get a few hits that use this wood plank wheel model. But I am extremely skeptical of these results: all the putatively medieval wood plank wheels are of modern constructions. They look like they’re meant to appear antiquated but are in fact not, which is exactly what I’m hypothesizing happened with Rings of Power.

All the actual medieval drawings I’ve found so far depict spoked wheels.

Yet in spite of Rings of Power’s poor design choice, I have a good idea as to why its showrunners chose this. I’m not completely certain, but I have a very good idea…

Here be Speculation

Full disclosure: I have no idea if this is right. I am totally theorizing as to why Rings of Power did this. That said, whether or not I’m right, this exercise will be constructive.

There’s one place where we do see this plank design, and that’s in Scandinavian (viking) round shields!

Here is where we see plank wood shaped into a perfectly round, perfectly flat form around a metal hub.3 Its design allowed it to effectively be used in a shield wall formation.4 Some researchers even hypothesize that this flat, round face was chosen so enemy weapons would “catch” in the wood and stick so that with a twist of the shieldbearer’s wrist the weapon could be wrenched away from the adversary.

It was not chosen to be mounted on an axle, wagon or otherwise. It’s a shield. Not a wheel.

If I had to guess what happened here – and again, this is just a guess – here’s what I think:

The writers conceived of this scene and pictured Sauron creeping onto a covered wagon. The artists got back to them, and the covered wagon looked a little less Lord of the Rings and a little more Oregon Trail.

See, Tolkien’s Middle Earth largely derives from an 11th century European aesthetic, which we can surmise given its weapons, armor, technology, and tactics. Hardly anybody (and ideally nobody) is explicitly thinking this while they’re reading / watching LotR or its derivative media, but associations like pinning down analog time periods are usually being made by the audience anyway at a subliminal level. For a writer to be explicitly conscious of them is therefore advantageous and worthwhile.

Meanwhile, we associate covered wagons mostly with the American Manifest Destiny movement of the 19th century. Seeing a spoked wheel might not feel right here (even if it technically is).

Interestingly, there is an exception to this rule, and it’s anywhere we encounter hobbits.

And look! In the visual media we often find them in The Shire!

Spoked wheels don’t feel so bad here, do they? That’s because The Shire evokes a 19th century English countryside aesthetic! In The Lord of the Rings’ first chapter, Tolkien describes Bilbo’s momentous birthday party as approaching like a “locomotive.” There are obviously no locomotives in Middle Earth, but this simile is meant to put us in mind of the green, bucolic dales of late 19th, early 20th century Britain, where the wagon wheels we’re discussing would feel right at home.

In contrast, here are some wains from Rohan and their wheels…

What you have there is much thicker felloes (less commonly spelled fellows), or interlocking pieces of wood to sit within the tire, run the wheel’s exterior, and route any shear forces along the outside. Its many joints gives it the elasticity to “breathe” and handle cyclical strain, something accomplished by the natural properties of rubber in modern tires.

For an extreme example of shear force at work on wheels, take a look at a drag racer in its first moments of acceleration when the torque-to-inertia ratio is highest.

Historically, wheels with extra thick felloes might have been used for heavy cannons5, but even bulky cannons usually got standard spoked wheels since one could expect handling compression loads to be far more urgent than shear (ie. supporting the weight on the axle takes priority over counteracting wheel deformations).

As it stands, the Rohan felloes might be a case of the artist making an exception in order to match audience expectations. If so, this is a great example of what I said before, that digressions from historical or literal realism typically work better when they are intentional rather than accidental. This could be a valid place to make a wheel that looks more mythical rather than being historically or functionally accurate. I personally would probably still stick with a spoked wheel with normal-sized felloes, but I can understand why one might make such a stylistic choice.

Now what about Rings of Power’s hobbits’ wheels?6

So instead of having spoked wheels which give off the wrong vibe, I hypothesize that Rings of Power’s design artists went with something they felt would look and feel closer to the intended setting.

I think they could have done better.

Brass Taxes: How to Improve?

We’ve just reached the good part. Here is where we stop simply criticizing and instead put on our creative hats.

Let’s imagine we’re show writers and we’re presented with this Sauron resurrection scenario. The covered wagon with its spoked wheels doesn’t look right, but the viking shield looks even more not rightier than the wagon’s not-rightiness! What do we do?

Well, if a covered wagon doesn’t feel right, the first question is, do we need it at all?

Sauron has just squeezed out of the mountainside. Presumably, this is part of the same massif as his bastion, which is going to be a very dangerous place for humans. But we need a human to be nearby for him to prey upon…

Let’s start there.

Why would said human be in such a perilous place? Maybe the story would be better served if this traveler were on foot, lost and afraid. Maybe she could be some sort of messenger, or at the very least hurrying through that place. And if she’s hurrying, then she wouldn’t be bringing all her effects with her, which means she no longer needs a covered wagon which is for more migratory purposes anyway.

But that begs the question, what does the land around Sauron’s estate actually look like? In the show it looks arid —almost like Rocky Mountains scrublands — but are there not farms? Where does his army get its food?

Fun fact: in the premodern world, 80-95% of people were farmers, and I wrote a whole worldbuilding guide on the implications of that and farming practices!

Worldbuilding Guide: Premodern Agriculture

Hello, I’m Ian Dunmore, and I write short fantasy stories, with the occasional piece on writing or worldbuilding.

Seriously: farmers are constantly getting neglected in these stories, both in fantasy and other genres. So many stories could benefit immensely from their inclusion. For details, read the article linked above.

If we had Sauron creeping out onto abandoned farmland, we’d actually get to see the consequences of his conquest and devastation, something we rarely get in the rest of the show!

Now pause. Look where we are.

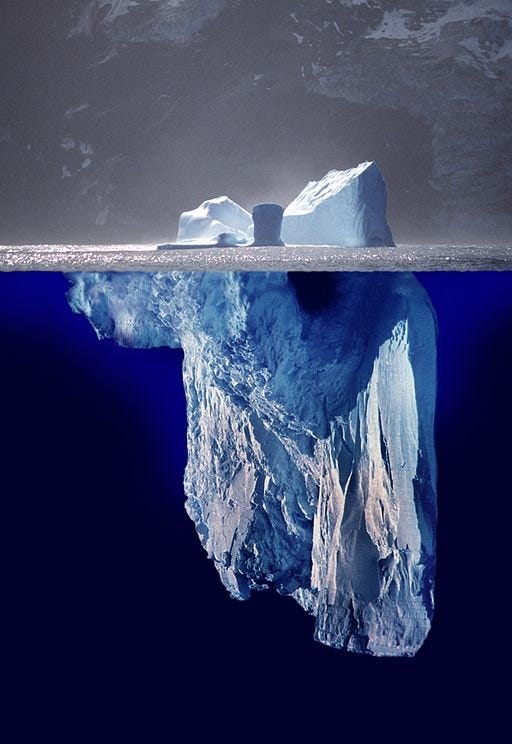

We asked a few prickly questions about a silly wheel, and suddenly we’ve arrived at some serious, pressing problems regarding worldbuilding. They might be difficult to answer in the short term, but if we can address them our story will be so much richer and we’ll have our immediate answer as well. This goes back to the old Iceberg Principle of worldbuilding, that most of the stuff you develop will remain “underwater,” not explicitly read / seen, but most certainly felt.

“Underwater” does not mean “unimportant.” Tolkien’s world is so wonderfully vivid precisely because it’s a world, and for all the immensity of his corpus we’re still only seeing a fragment of it. That’s a good thing! That makes stories incredibly compelling!

But how ‘bout that wagon?

The wagon itself presents both obstacles and opportunities for us in this scene.

The original script calls for Sauron to creep aboard and gank the driver. That would certainly startle the horse. And unlike my misbehaving toddler on the interstate, the horse has no red button to instantly release its restraints, but the moment Sauron showed up in Venom-form it would probably bolt.

Can the historical sources give us some grounding ideas here? Absolutely! For starters, horses were not the only options in terms of hauling animals!

If it’s not a horse but is instead a cow or ox, it’s not going to run very fast. Also, because terrain, there’s a real possibility it could get injured if it flees. The beast not running quickly or injuring itself could solve the problem of the next scene, where the showrunners clearly wanted to get a dusky shot of Human Sauron weeping moodily while staring into his smol campfire. It’s also a great opportunity to show some of Sauron’s character: what does he do if the animal injures itself?

Kill it and eat it?

Abandon it?

Put it out of its misery?

Watch it slowly languish and perish and contemplate the inferiority of the mortal world?

This hazard of uneven terrain is even higher for the wagon itself than the animal. Any wheeled transportation device is not going far off the well-trodden road – case in point, the Oregon Trail wagon trains adhered so closely to their predecessors’ paths that there are literal grooves worn in stone that you can still find today!

Wheels are expensive, difficult to make, and in the wilderness a broken wheel could equal death. The same will be true for the hapless woman in our scene.

Alternatively, if we go the route of this woman being lost or desperate, then that yields other options. It might be more logical for her to be walking alongside not a wheeled device like a wagon or wain, but something more like a travois.

Travoises were used precisely for such situations where the traveler could not count on level terrain. They could even be attached to dogs, meaning that an expensive pack animal is unnecessary. It runs the risk of looking too Native American, but if done right it solves almost every problem and could be a unique and novel addition to the world the showrunners are going for!

Now look again at where we are. We started with a questionable-looking wheel, and by tugging at historical strings we’ve arrived at opportunities for character, story and world.

This is how it works.

The Complete Picture

So, having gathered all this information, here’s what Ian Dunmore would have done with this wagon scene if he were given carte blanche:

No wagon. The woman is a desperate, frightened scavenger. She must be desperate and frightened, hence why she’s so near to Sauron’s base! The area she finds herself in is wartorn and abandoned, with fallow farmlands under the chilly snow — having the outside be war-ravaged seems logical given Sauron’s own men are now turning on him, and this way we get to actually see some of Sauron’s handiwork instead of just hearing tell of it. She has a cow with her, hitched to a travois she’s piling up with tchotchke. No more wheels.

The cow senses Sauron coming and tries to run, but she holds it back, telling it to get a grip even though she too is getting anxious. Venom Sauron grabs her. The cow runs, dragging along the travois which is racketing off obstacles and throwing objects everywhere. But the cow quickly stumbles on the stony ground. Sauron transforms into Human and walks up to the cow, which is injured and dying. He stares at it in disgust.

Then we cut to the fire.

And All This from a Wheel

Before we close out, I’d like to make the point that none of the revisions proposed above in any way drastically altered the plot, nor did they cost any more screentime than was allotted. A desperate woman with a travois is not the only way of doing this, there are certainly any number of ways. My point is that the scene as it currently stands is a missed opportunity to make the setting deeper, and would have been better served with some application of historical nitpicking.

The wagon is onscreen for about a minute and a half, and any of what we’ve discussed could be incorporated in that same amount of time to great effect. Had the decision-makers sat down to critically think about this wagon business and compare it to the available historical counterparts, they might have arrived at not only something more logical, but something that resonated as an event that could be believed in.

And that process doesn’t need to begin at an enormously high level. Often enough, it doesn’t. In fact, it usually begins with stubbornly chasing after the answers to petty questions. Sometimes this can feel like splitting hairs, or like getting fussy and wanting a story to fail, but it doesn’t have to be! If you have something in your specific world that just doesn’t quite feel right, don’t ignore it! Delve deeper, follow that rabbit down the hole. In the long run, your story will be better for it.

Thanks for reading! If you liked this article, you might like the following on exposition:

Subscribe to Dunmore Dispatch for fantasy fiction delivered every other week!

That said, Miyazaki’s films feature some extraordinary realism in many of their details even amid their high-concept fantastical elements, which is exactly my point!

Spokes also allow for control over how the wheel is “dished,” which will ensure longevity over time. They’re also lighter. They’re also oval, not perfectly circular. The list goes on.

In contrast to other shield designs that were square and/or convex.

Although the “wall” portion of the name has been taken far too literally in much entertainment media.

I’m ready to be corrected, but I found no historical instances of this.

Totally beyond this essay’s scope, but this same historical nitpicking could be applied to the hobbits as a whole to powerful effect. Where are they getting iron cookwear and textiles? Let’s talk about that sometime!

an incredible look into how the cumulative and compounding effects of small details, oft unnoticed, can impact how we percieve a world. Either we immerse in it, or always feel that something is not quite right. Excellent insight as always Ian!

Hoo boy, if you think the wagon wheels are bad, you should see some of the "armor" they slap on these characters.