The Forgotten Narrative Tool: Variable Zoom

It's not either tight or broad. It's both.

My friend Eric Falden wrote an excellent piece on narrative distance, a concept he and I have been discussing almost nonstop since we learned of it. In brief, narrative distance is the proximity of the narration to its subject’s action. Falden quite effectively likened this to a lens or scope, and how far the observer is from the event dictates the narrative distance. It’s not the same as narrative voice, which is who’s telling the story and in what tone and with what biases. Narrative voice and narrative distance are related, but not the same.

Here I’m going to argue for the use of what I’m going to call variable zoom, which I believe to be a scandalously underutilized tool in contemporary fiction.

But what actually is narrative distance?

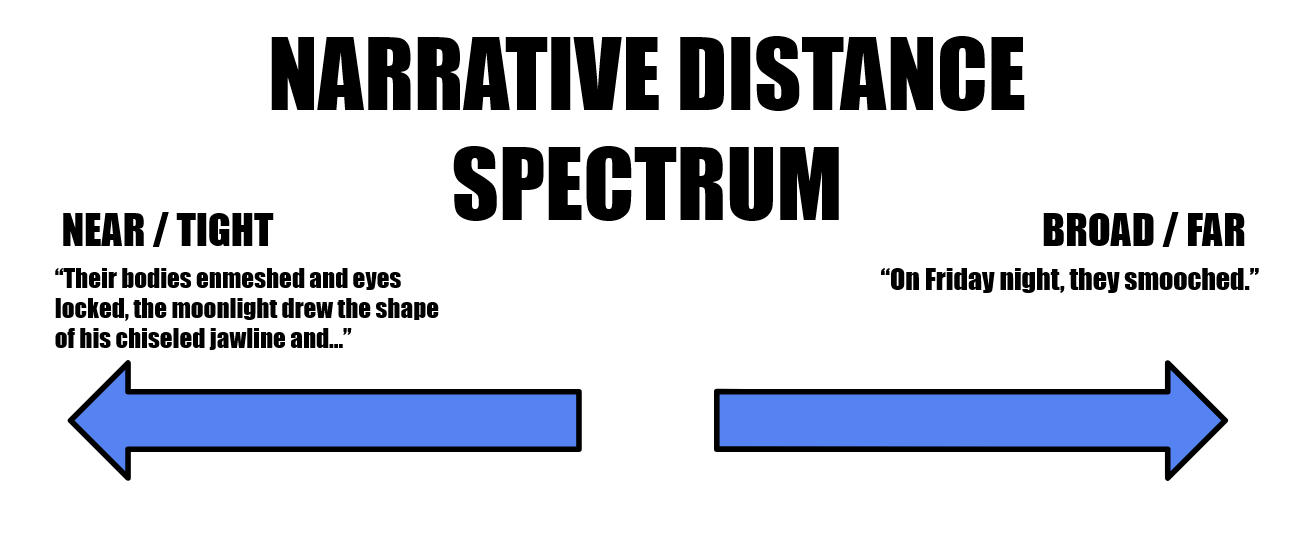

Let’s look at the two extremes.

A “close” or “tight” narrative distance will result in a scene that’s high on detail and is grounded in the immediate experiences of the characters. Dialogue, for example, almost always indicates a tight narrative distance. A “broad” or “far” narrative distance makes for overviews or generalizations.

In his article, Falden points out that this device helps explain why some narrative choices restrict the writer’s ability to convey things like context. Many writers choose present tense, but doing so requires a continuously tight narrative distance because everything that occurs in the present is by necessity happening right now.

At the opposite extreme, an epistolary device literally means the narrator is in a temporally and often physically separate place such that the action has occurred at a distance, and therefore tends to be more cursory.

Neither of these devices are bad, but they do constitute stylistic conceits that limit the author’s choices. They “fix” the narrative distance to a certain point, whether tight or broad.

But ideally, a narrative would allow for variable zoom.

Variable Zoom

Variable zoom is where the narrative distance is able to glide or jump between near and far at will. It’s not locked or fixed like a video game camera, where the audience can only experience precisely what the POV character is experiencing in the moment. In one sentence, it can cover great spans of time or distance, and in the next bring the reader straight down into the character’s shoes to observe something up close.

Far to Near

By way of example, take the following section from Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, where the main character known only as the kid is wandering the southwestern American desert with an injured and languishing companion named Sproule:

They descended the mountain, going down over the rocks with their hands outheld before them and their shadows contorted on the broken terrain like creatures seeking their own forms. They reached the valley floor at dusk and set off across the blue and cooling land, the mountains to the west a line of jagged slate set endwise in the earth and the dry weeds heeling and twisting in a wind sprung from nowhere.

They walked on into the dark and they slept like dogs in the sand and had been sleeping so when something black flapped up out of the night ground and perched on Sproule’s chest. Fine fingerbones stayed the leather wings with which it steadied as it walked upon him. A wrinkled pug face, small and vicious, bare lips crimped in a horrible smile and teeth pale blue in the starlight. It leaned to him. It crafted in his neck two narrow grooves and folding its wings over him it began to drink his blood.

Not soft enough. He woke, put up a hand. He shrieked and the bloodbat flailed and sat back upon his chest and righted itself again and hissed and clicked its teeth.

The kid was up and had seized a rock but the bat sprang away and vanished in the dark. Sproule was clawing at his neck and he was gibbering hysterically and when he saw the kid standing there looking down at him he held out to him his bloodied hands as if in accusation and then clapped them to his ears and cried out what it seemed he himself would not hear, a howl of such outrage as to stitch a caesura in the puslebeat of the world.

Take a look at how McCarthy expands and contracts narrative distances. The first paragraph begins at a far distance, covering a day and half a night in seventy-three words. The next paragraph zooms in a little, then settles onto a vampire bat alighting on Sproule. The first sentence of paragraph three (“Not soft enough.”) shoots us straight back into Sproule’s head as he wakes up in utter horror, then paragraph four zooms out again to give us an omnipotent view of the desert and their insignificance in this unforgiving universe. All this is accomplished in under three-hundred words.

Now imagine if McCarthy hadn’t used a variable zoom technique, and instead had fixed his narrative distance.

A broad distance throughout would have been over in just a few words: “As they slept in the sand in the frozen night, Sproule was visited by a vampire bat who bit his neck, but he woke during the feeding and howled into the emptiness with hands bloodied and outstretched.”

A tight distance throughout could have gone one of two ways:

It could have taken thousands more words to little benefit.

It would have skipped the description of their travels and begun with Sproule waking up, which would have detracted from the harshness of the setting.

Near to Far

A second example, with a light spoiler for the opening of Guy Gavriel Kay’s Tigana.

The despotic, autocratic sorcerer Alberico has crashed a seditious meeting of nobles who seek to overthrow him. Several of the nobles futilely draw weapons on him, while others like the crippled Lord Scalvaia can only watch. It looks like a one-sided bloodbath with Alberico slaughtering the conspirators, until this happens:

And then, just then, with all eyes on [the last noble who just died], Lord Scalvaia did the one thing no one had dared to do. Slumped deep in his chair, so motionless they had almost forgotten him, the aged patrician raised his cane with a steady hand, pointed it straight at Alberico’s face, and squeezed the spring catch hidden in the handle.

The moment pauses, suspended at this heartstopping interval. The author talks about sorcerers and their powers in very general and blunt terms, and we the readers stick around for it because our knuckles are standing white. This is indeed a perfect place for such blunt exposition — Raw Veggies Exposition, I call it. It’s another criminally underutilized tool in today’s fiction.

Back to Tigana. After some well-placed expostion, we get this…

It is the simple truth that mortal man cannot understand why the gods shape events as they do. Why some men and women are cut off in fullest flower while others live to dwindle into shadows of themselves. Why virtue must sometimes be trampled and evil flourish amid the beauty of a country garden. Why chance, sheer random chance, plays such an overwhelming role in the running of the life lines and the fate lines of men.

It goes on: philosophy and poetry regarding those interstitial moments that bend the arc of history. GGK has the reader in his palm and he knows it. Out, out, out he zooms, even while we’re screaming to get closer and find out what happens next.

When he does fly back in, the payoff is satisfying indeed.

C’mon Ian, isn’t this just omniscience?

Some might argue so. The last two examples I gave were both that, after all. But no, narrative distance and narrative voice are different. Related, but different.

A semi-omniscient narrative voice is most conducive to variable zoom narrative distance, but it isn’t necessary. The Kite Runner is full of great examples of variable zoom, and that story is written in first-person. In fact, almost all stories written in past tense are capable of variable zoom. Classic literature used variable zoom all the time. When some people complain about classic lit being boring, what they mean is that the narrative distance never got near enough for them to care. It remained far for the duration, with dignity if not excitement.

Maybe you think that narrative distance is just omniscience with extra steps, but I’ll say this: you can have an omniscient story with fixed narrative distance… I don’t know why you would, but you could. Falden’s point in his essay was to explore the reciprocal: you cannot have variable narrative distance with any point-of-view you please. Some viewpoints – like the aforementioned first-person or epistolary – are by their very nature restrictive.

On the other hand, it’s worth noting that allowing for omniscience or semi-omniscience allows an author to n-zoom, something that’s not possible to its fullest extent in any other medium other than literature.

My question, therefore, is why don’t more contemporary stories use variable zoom? Why in contemporary fiction has variable zoom been almost totally forsaken?

The FND

Perhaps I’m just underread, but I can think of very few novels written in the past twenty years that use this tool. The overwhelming majority are written with FND (Fixed Narrative Distance), Falden’s Video Game Camera.

For example, take a highly mainstream work of fantasy, Sarah J. Maas’ Throne of Glass. Here’s a small quote from it, with the setup being the main character Celaena writing to the Crown Prince at the other side of the castle they’re both in to request some reading materials. First we watch her write her note, then when she’s finished…

Celaena beamed at her note and handed it to the nicest-looking servant she could find, with specific instructions to give it immediately to the Crown Prince. When the woman returned half an hour later with a stack of books piled in her arms…

These two sentences together are perfectly serviceable, but in the context of the book and its style, they were wholly immersion-breaking. For me, reading them was like hitting a speed bump on a highway.

Throne of Glass is written at a tight — and fixed — narrative distance. That means everything that happens, all exposition that gets delivered, every byte of data the reader needs, can only be transmitted through known characters who are presently engaged in something. To demonstrate our contestant’s struggles with the rigorous training, we have to see her hidden by the side of the running trail bent over and vomiting. We could have gotten a training montage, but alas, we’ve committed to not zooming out, so instead we need a demonstrative anecdote.

It was so fixed, in fact, that the moment the narration digressed from being fixed, it ruptured my immersion. The time leap (“When the woman returned half an hour later…”) might have been needed because nothing relevant transpires while waiting for the courier to return, but the FND style lacks the elasticity to handle it.

So committed was the rest of the book to FND that, to get an outside description of the castle, the heroes have to be camped outside of it, looking at it. This is precisely what Maas does, and it takes the better part of four pages.

Let’s run with this example of looking at the castle, and let’s imagine what it might read like if written with variable zoom. In this little rewrite of mine, I don’t want you to focus on the prose (hence why I’ve bracketed much of the exposition), but instead get a sense of how the narrative distance is dynamically collapsing and extending:

The castle rose gleaming above the surrounding countryside, its [DESCRIBE THE CASTLE HERE]. Even from far off, Celaena’s first view of it took her breath away such that she could not stop staring at its apparition wherever it emerged between or above the trees, all the way through the afternoon and into evening. They camped a few miles from its base still within the forests’ reaches, but as the fire died and her escorts fell one-by-one into sleep, still Celaena sat staring at that diadem of stone and glass deep into the night.

Dorian Havilliard watched her with one hand on his sword, his wits demanding suspicion but his heart whispering something else of this lovely girl staring at the stars and the castle beneath them. [BACKSTORY ON DORIAN HERE].

Finally he spoke to her: “What are you looking at?”

[INSERT SWOONWORTHY REPARTEE]

“Well,” he said, lying down again, “we’ll know that when we reach the castle.”

Celaena’s marvel only grew the next morning as they passed beneath the gatehouse and into the…

You get the idea. This might not match Maas’ style or tone, nor might it be particularly well-written. I share it as a proof of concept that variable zoom can be utilized to adjust the narrative distance without loss of meaningful content.

***

As a second example, take Brandon Sanderson’s Words of Radiance, the second book in his Stormlight Archive series. I’ll be cursory to avoid spoilers: in a given passage, two main characters spend half a chapter wandering a menagerie that’s recently set up near their army camp. Some worldbuilding exposition and character interaction happens.

Then in the chapter’s closing sentences we get a cliffhanger: our characters hear shouting from one end of the menagerie. They turn to see another main character entering and shouting for the crowd to make way as he leads in the newly appointed head of their organization who happens to be (gasp) a manifest villain.

This jarred me. Why was this momentous announcement being made at a menagerie? And how serendipitous that it would occur at the same time as our other heroes were nearby and together to witness it. The improbability broke my immersion.

It could have been otherwise. A little in-and-out zoom could have taken them back to their main locale where they could have seen a crowd and heard the announcement in a more appropriate context. But, because this story committed to FND, everything had to happen in these discrete chunks. The narration couldn’t zoom out to talk about character relationships at a higher level (unless the character was sitting somewhere pondering said relationship in the moment). Its stylistic choices had already railroaded it into scooping together all these important moments into single, enormous scenes where plot points emerge and disappear like a shooting gallery, no matter how improbable that might be in reality.

Once again, my immersion fled the scene.

FND = Bad Writing?

I want to be clear that I’m not saying that these books or any other writing is automatically bad for maintaining FND. I know people who prefer this style, and as I said before, Maas and Sanderson are far from the only writers doing this. FND is so nearly universal that it wouldn’t surprise me if someone told me that editors and publishers encourage or enforce it. I just don’t understand why.

Some have told me it makes the story more immersive. I would argue against this; it can make scenes and moments more immersive, but the overall story has to then handle the technical drawbacks I’ve described above. Also, this is not a zero-sum game, and that is my entire point. The example from Blood Meridian shows how writers can do both: zoom in for the visceral parts and zoom out for the more general moments. It doesn’t need to be either tight or broad. Each lens should be used where appropriate. Sometimes writing certain individual scenes at a fixed distance can be a powerful tool.

So why don’t we?

It’s also possible that FND is so ubiquitous because it makes outlining much easier. Outlining with FND allows the author better precision and organization in terms of knowing exactly when and how things happen. It also better matches visual media, which far more of us regularly consume. In cinema, everything must happen onscreen (or be rendered by absence), just like how FND requires everything to happen in a scene. It’s much easier to take stories written with FND and adapt them to screenplays.

But even films exercise a modicum of variable zoom that FNDs often don’t. Movies still have training montages. The camera can pan over crowds of people glued to news broadcasts without mandating a main character be there to witness it. An establishing shot to precede a movie scene is pretty standard stuff, but in order to get a good look at the main castle Throne of Glass requires an entire scene where Celaena must be camped outside the castle looking at it.

Jump cuts in cinematography work. But FND is more akin to a long take or a “oner,” where the camera never cuts. Long takes can be used to great effect, but use them all the time and their limitations become apparent. In this way, FND stories sometimes read less like written tales seeking a screenplay adaptation, and more like novelizations of existing screenplays. Of all Cormac McCarthy’s novels, the one that most adheres to FND throughout is No Country for Old Men; would it surprise you to know he originally wrote it to be a screenplay?

Every form of media has its advantages and disadvantages. In my opinion, “variable zoom” narrative distance is one of the greatest advantages of the written word over other storytelling forms. I would rank it all the way up there with “ability to explicitly disclose subjective experience.”

I just wish it got used more.

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t read Eric’s article which kicked this off, you should do so now!

Feel free to comment with your own thoughts at an appropriate distance, and check out my follow-on article to this one for more:

To get an attempt at Variable Zoom in my own work, here’s a piece I wrote that involved its utilization:

And as always, subscribe for more musings like this, but especially some fiction that hopefully has a multiple zoom function!

This is an excellent post! Going into my saves to read again later good.

"FND is so nearly universal that it wouldn’t surprise me if someone told me that editors and publishers encourage or enforce it." Agents and editors have been hammering this is as the one true way for decades. I started the author thing in the early 2000's, and this was the gospel they preached then and in the 90's. When I had an agent between 2004-2008, I was advised on one story to zoom in more. At that time, nearly everything coming out in genre was third-person limited with even first-person being quite rare.

I believe it is still the common advice given. Deep POV is a very popular topic in the romance writing community, and I have read a couple of books on writing in this style. And people are going to write in the style they most commonly read, so it's self-perpetuating.

I've been so happy to read this article and Eric Falden's, because these are things I am focusing on for upcoming books and a book of mine that I am currently updating. I can't change the style I'm using in ongoing series, of course.

In the first disgustingly long novel I wrote (unpublished and seen by few save for an agent and a few editors) I started every chapter zoomed out and then brought the viewpoint in tight. It might have been one of the things holding me back in their world at the time.

A great post!

I really enjoyed (especially) your break down of Blood Meridian. He does that all the time (and I never really thought about it). You would think the zoom in/zoom out in such a tight word count would read like a janky rollercoaster. But I think it actually adds to the sweepingly epic feel of the novel.

I am reminded of The Battle of The Five Armies scene in The Hobbit. I remember feeling like it didn't quite fit... Maybe that's because it's one of the few times Tolkien pulls back the narrative view. (It's been a long time since I read that, though.)

You say authors tend to hold the camera really close. I wonder if this is because with a broader narrative view, it feels like telling vs. showing (even if it's not)?